The hum of cooling fans has long been the defining soundtrack of data centers worldwide. For decades, air cooling has been the default, the comfortable and well-understood method for managing the immense thermal output of computing equipment. But as computational demands skyrocket—driven by artificial intelligence, high-performance computing, and ever-denser server architectures—the limitations of moving air have become starkly apparent. We are rapidly approaching a thermal ceiling, a point where air can no longer carry away heat efficiently enough. In this new era, the industry is turning to a more fundamental and powerful medium: liquid. The transition to liquid cooling is not merely an incremental upgrade; it represents a fundamental paradigm shift in data center design, deployment, and operational philosophy.

The rationale for this shift is rooted in simple physics. Liquid, specifically water, has a heat transfer capacity that is orders of magnitude greater than air. It can absorb vastly more heat and transport it away from components far more effectively. This superior thermal performance directly translates into tangible benefits. Firstly, it enables higher compute densities. Servers can be packed more tightly without fear of overheating, drastically increasing processing power per square foot. Secondly, it dramatically improves energy efficiency. The energy-intensive choreography of computer room air handlers (CRAHs) and fans, which can consume up to 40% of a data center's total power, is significantly reduced or even eliminated. This reduction in power usage effectiveness (PUE) is a critical goal for operators facing both rising energy costs and increasing pressure to meet sustainability targets.

The journey begins not on the data center floor, but in the design phase, where the foundation for a successful liquid-cooled deployment is laid. This phase demands a holistic and integrated approach, a stark departure from the more siloed planning of air-cooled facilities. The first and most critical decision revolves around the cooling architecture itself. Will the implementation use direct-to-chip (DTC) cooling, where cold plates are attached directly to high-heat components like CPUs and GPUs, and a dielectric fluid is pumped through a closed loop to remove heat? Or will it employ immersion cooling, where entire servers are submerged in a bath of dielectric fluid that boils at a low temperature, carrying heat away through phase change? Each method has its proponents and specific use cases, with immersion often reserved for the most extreme high-density applications.

This architectural choice then dictates a cascade of other design considerations. Facility infrastructure must be re-evaluated. Raised floors, a staple of traditional data centers for distributing cold air, may become obsolete. Instead, designers must plan for the distribution of coolant—the pipes, manifolds, and quick-disconnect fittings that will form the facility's new circulatory system. Questions of materials compatibility, leak detection, and drainage become paramount. The structural load of the floor must be calculated to support the significant weight of immersion tanks or the additional plumbing. Power distribution also changes; with fans largely removed from the equation, power can be delivered more directly to the silicon, but new demands are placed on pumping power for the coolant.

Once the blueprints are finalized, the deployment phase presents its own unique set of challenges and procedures. Unlike air cooling, which is largely a macro-environmental concern, liquid cooling is intensely intimate with the IT hardware. For direct-to-chip systems, this means the careful installation of cold plates on each server component. This process requires precision, training, and a new set of skills for the data center technicians, who must now be as comfortable with fluid dynamics as they are with rack-and-stack procedures. Meticulous pressure testing of all loops is essential before the system is charged with coolant to prevent catastrophic leaks.

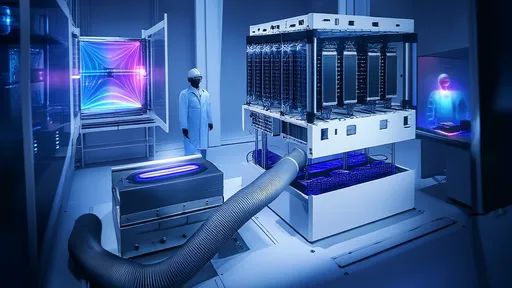

Deploying an immersion system is an even more profound change. It involves lowering entire servers into a specially designed tank filled with dielectric fluid. This act alone requires new handling equipment and protocols. The servers themselves are often custom-built or heavily modified for immersion, with all air-cooled components like fans and heat sinks removed. The entire operational workflow, from server provisioning and maintenance to decommissioning, is transformed. A failed drive or memory module is no longer a simple hot-swap; it involves safely extracting a server from the tank, draining and cleaning components, and performing the repair before re-immersing. This necessitates rigorous new safety protocols to protect technicians and the environment from fluid exposure.

Perhaps the most significant cultural shift occurs in the ongoing maintenance and operation of a liquid-cooled data center. The day-to-day rhythm of the facility operations team changes completely. Their focus shifts from managing air temperature and humidity setpoints to monitoring fluid dynamics. The health of the system is now gauged by metrics like flow rate, pressure drop, inlet and outlet coolant temperatures, and the quality of the fluid itself. Continuous monitoring for particulates, conductivity, and biological growth within the coolant loops is critical to prevent blockages or corrosion.

Maintenance is no longer just about replacing air filters and checking condenser units. It involves scheduled flushing of loops, replacing filters on the fluid distribution unit (FDU), and verifying the integrity of thousands of connections. Advanced predictive maintenance, using sensors and analytics to forecast pump failures or detect minute leaks long before they become critical, becomes a core competency. The skill set required for these roles evolves, demanding knowledge of mechanical systems and chemistry alongside traditional IT and facility management expertise. This often necessitates significant investment in training existing staff or hiring new specialists, fundamentally reshaping the data center team.

Looking forward, the adoption of liquid cooling is accelerating from a niche solution for supercomputers and cryptocurrency mining to a mainstream strategy for enterprise and hyperscale cloud providers. The drivers are undeniable: the unrelenting growth of AI model training and the industry-wide shift towards more powerful, heat-dense processors from all major manufacturers. The future will likely see a hybridization of approaches, with liquid cooling handling the high-density compute and air cooling supporting the remaining infrastructure. We may even see the rise of "waterless" data centers in water-scarce regions, using alternative coolants or advanced dry-cooler systems.

The move to liquid is more than a technical decision; it is a strategic one. It future-proofs data center infrastructure, allowing it to scale to meet the computational demands of the next decade. It offers a clear path to radical efficiency gains, slashing operational expenses and carbon footprints simultaneously. While the initial investment and cultural change required are substantial, the long-term benefits in performance, density, and sustainability position liquid cooling not as an alternative, but as the inevitable next chapter in the evolution of the data center. The era of whispering fluids is quietly dawning, ready to replace the roar of fans.

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025