The relentless pursuit of computational speed has long been a defining feature of the technology industry. For decades, this pursuit was largely satisfied by the predictable cadence of Moore's Law, which delivered ever-increasing numbers of transistors on a single chip, allowing processors to execute instructions at breathtaking speeds. However, a fundamental and increasingly critical imbalance has emerged, casting a long shadow over these advancements. The core of the problem is not the speed of computation itself, but the agonizingly slow and power-hungry process of moving the data needed for those computations. This is the infamous "data movement bottleneck," a wall that traditional computing architectures are repeatedly crashing into.

At the heart of this bottleneck lies the von Neumann architecture, the foundational blueprint for nearly all modern computers. This design strictly separates the central processing unit (CPU), where calculations happen, from the memory hierarchy (caches, DRAM, storage), where data resides. While this separation offers flexibility, it creates a performance chasm. A CPU can perform an operation in a fraction of a nanosecond, but fetching the data for that operation from main memory (DRAM) can take hundreds of times longer. This wait time, known as latency, forces powerful processors to sit idle, wasting energy and potential. The energy cost is staggering; studies have shown that moving a single byte of data from main memory to the CPU can consume orders of magnitude more energy than the actual computation on that byte. As we enter the era of data-intensive workloads like artificial intelligence, machine learning, and massive data analytics, this bottleneck is no longer a minor inefficiency; it is the primary limiter of performance and scalability.

In response to this growing crisis, a paradigm shift is underway, moving away from the traditional compute-centric model toward a more data-centric approach. This shift is embodied by Near-Memory Computing (NMC), a revolutionary architectural concept gaining tremendous traction in research labs and industry. The core philosophy of NMC is elegantly simple: instead of forcing data to make the long, costly journey to a distant processor, bring the computation capabilities directly to where the data resides—inside or extremely close to the memory itself. By colocating logic and memory, NMC seeks to drastically reduce data movement, slashing both latency and energy consumption, and ultimately unleashing the true potential of modern processors.

The implementation of Near-Memory Computing is not a single, monolithic technology but rather a spectrum of architectural innovations. On one end of this spectrum lies Processing-in-Memory (PIM), the most integrated form of NMC. PIM involves embedding processing elements directly into the memory die or memory array. Imagine a DRAM chip where, alongside the billions of memory cells, there are simple arithmetic logic units (ALUs) or more complex cores. These processors can perform operations on the data stored in adjacent memory cells without ever sending that data across the memory bus. This approach minimizes distance to an extreme, offering the highest potential gains in bandwidth and energy efficiency. However, the challenges are significant, involving complex changes to memory manufacturing, heat dissipation in dense arrays, and programming models to effectively utilize these distributed, heterogeneous resources.

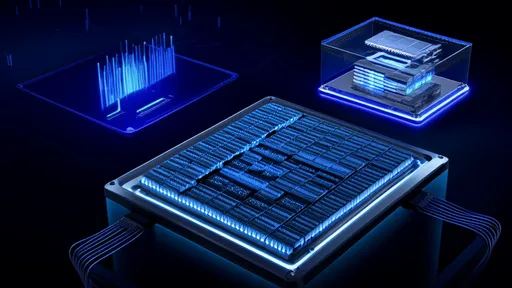

A more immediately practical and widely adopted approach is found in the concept of Near-Memory Processing, often used interchangeably with NMC but sometimes denoting a slightly less integrated solution. Here, specialized compute units or accelerators are not placed inside the memory array itself but are placed on the same package or interposer as the memory stacks, connected via incredibly dense and fast interconnects like silicon vias. A prime and commercially successful example of this is the integration of high-bandwidth memory (HBM) with GPUs and AI accelerators. The GPU die is surrounded by stacks of HBM, connected through an interposer that provides a massively wide data path. While the data still moves from the memory stack to the processor, the distance is measured in millimeters instead of centimeters, and the available bandwidth is orders of magnitude greater than a traditional DDR memory bus. This architecture has been instrumental in enabling the teraflops of performance required for training large neural networks.

The real-world impact of Near-Memory Computing is most visible in the fields of artificial intelligence and big data. AI models, particularly deep neural networks, are inherently memory-bound. Their operations involve massive matrices and tensors that must be shuttled between memory and processors. NMC architectures are a perfect fit. Companies are developing specialized PIM chips for inference workloads, where the model's parameters are stored and computed upon within the memory, leading to unparalleled throughput and efficiency. Similarly, for database operations and data analytics, tasks like scanning, filtering, and joining large tables involve moving enormous datasets. Performing preliminary filtering operations inside the memory bank, before the results are sent to the CPU, can reduce the volume of data movement by 90% or more, dramatically accelerating query times.

Despite its immense promise, the widespread adoption of Near-Memory Computing faces a set of formidable hurdles. The first is the sheer complexity of design and manufacturing. Modifying well-established memory fabrication processes to include logic elements is a non-trivial task that increases cost and risk. There are also significant programming challenges. The computing landscape is built around the von Neumann model. Writing software that can efficiently partition tasks between host CPUs and dispersed NMC units requires new languages, compilers, and frameworks—a fundamental shift in how programmers think about problem-solving. Furthermore, questions of memory coherence and data consistency between the host processor and the NMC units must be elegantly solved to ensure correct operation.

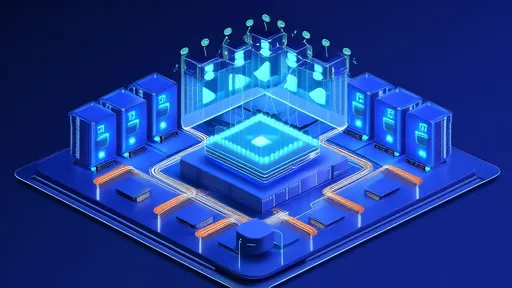

Looking toward the future, the trajectory of Near-Memory Computing is one of increasing integration and specialization. The industry is moving beyond simple proof-of-concepts to serious commercial exploration. We can expect to see the first wave of products focusing on specific, high-value workloads like AI inference and graph processing, where the benefits are most pronounced. Research is also pushing into more advanced concepts, such as leveraging emerging non-volatile memory technologies for NMC, which could blend storage and memory into a single, computable tier. In the longer term, NMC is not seen as a replacement for the CPU but as a critical component of a heterogeneous computing fabric. In this future system, workloads will be dynamically orchestrated across a suite of specialized units—general-purpose CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs, and various NMC accelerators—with data flowing intelligently to the most efficient location for processing.

In conclusion, the data movement bottleneck represents one of the most significant challenges in modern computing. Near-Memory Computing emerges not merely as an incremental improvement but as a necessary architectural evolution to overcome this hurdle. By fundamentally rethinking the relationship between computation and data storage, NMC offers a path to break free from the constraints of the von Neumann architecture. It promises a new era of computing efficiency, enabling the next generation of data-intensive applications that would otherwise be hamstrung by the limitations of data mobility. While the path forward involves overcoming substantial technical and ecosystem challenges, the pursuit of near-memory computing is undoubtedly a cornerstone of the future of high-performance and energy-efficient computing.

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025

By /Aug 26, 2025